Probability Trees

I recently interviewed for a data scientist/machine learning engineer position, and was asked this common interview question.

A patient is getting tested for a rare disease that afflicts 1% of the general population. The test has a 99% true positive rate and a 99% true negative rate. Given that the patient tests positive, what is the probability that they have the disease?

One of the most intuitive ways to solve this problem is to try it out with an actual number, say population of 10,000.

| Number of people who have the disease: | $0.01 * 10000 = 100$ |

| Number of people who will test positive: | $0.99 * 100 = 99$ |

| Number of people who don’t have the disease: | $0.99 * 10000 = 9900$ |

| Number of people who will test positive: | $0.01 * 9900 = 99$ |

| Total number of people who tested positive: | $99 + 99 = 198$ |

| Actual number of people who have the disease: | $99/198 = 0.5$ |

Another way is to apply Bayes’ theorem. Let $D$ be the event that one has the disease, and $P$ be the event that one tests positive.

\[P(D|P) = \frac{P(P|D) \cdot P(D)}{P(P)}\]Data:

\(\text{TPR} = P(P|D) = 0.99\)

\(\text{FPR} = P(P|D^C) = 0.01\)

\(P(D) = 0.01\)

For the probability that you test positive, we can apply Law of Total Probability:

\[P(P) = P(P|D) \cdot P(D) + P(P|D^C) \cdot P(D^C)\] \[\Rightarrow 0.99 \cdot 0.01 + 0.01 \cdot 0.99\]This gives us:

\[P(D|P) = \frac{0.99 \cdot 0.01}{0.99 \cdot 0.01 + 0.01 \cdot 0.99}\] \[\Rightarrow 0.5\]Note: This is a fairly surprising result; given that the accuracy of the test is pretty high, one expects a higher chance of having the disease if one tests positive. However, the rarity of the disease (1%) offsets the high TPR and TNR.

While both these approaches lead us to the correct solution, there is a better and more convenient way of solving the problem that is both mathematically rigorous (unlike the first solution), but also equally intuitive.

Probability Trees

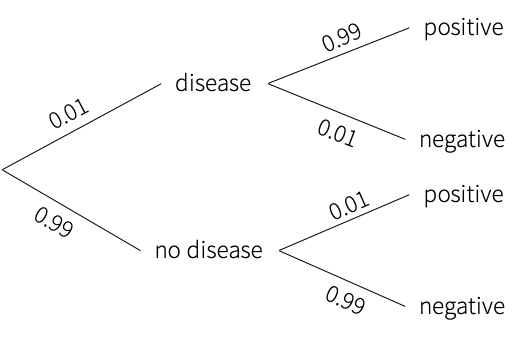

Let’s visualize the above problem in the form of probability trees:

The probability of testing positive is given by following all the branches that lead to testing positive, and adding them:

\[P(P) = 0.99 \cdot 0.01 + 0.01 \cdot 0.99\]The probability that we have the disease if we tested positive is given by looking at all the branches where this is true:

\[P(D \cap P) = 0.01 \cdot 0.99\]Thus the probability that we have the disease given that we tested positive is given by dividing the latter by the former:

\[P(D|P) = \frac{0.99 \cdot 0.01}{0.99 \cdot 0.01 + 0.01 \cdot 0.99}\] \[\Rightarrow 0.5\]This methodology applies for several problems that are common interview questions. It draws directly from the fact that

\[P(A|B) = \frac{P(A \cap B)}{P(B)}\]Let’s look at a few more examples:

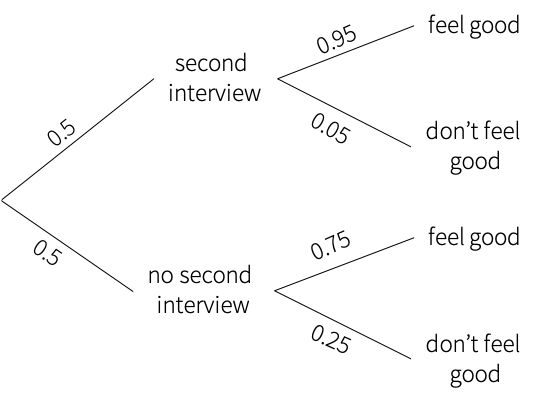

Suppose you were interviewed for a technical role. 50% of the people who sat for the first interview received the call for second interview. 95% of the people who got a call for second interview felt good about their first interview. 75% of people who did not receive a second call, also felt good about their first interview. If you felt good after your first interview, what is the probability that you will receive a second interview call?

By applying a similar approach of following appropriate branches, the answer is given by:

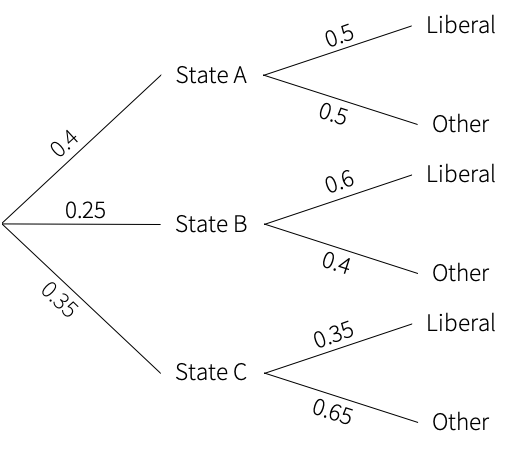

\[P(SI|FG) = \frac{0.5 \cdot 0.95}{0.5 \cdot 0.95 + 0.5 \cdot 0.75}\] \[\Rightarrow 0.55882\]Suppose a voter poll is taken in three states. In state A, 50% of voters support the liberal candidate, in state B, 60% of the voters support the liberal candidate, and in state C, 35% of the voters support the liberal candidate. Of the total population of the three states, 40% live in state A, 25% live in state B, and 35% live in state C. Given that a voter supports the liberal candidate, what is the probability that she lives in state B?

Summary

This is not a new concept, but it showcased how certain problems are far more simpler and intuitive if visualized appropriately. It is easy to get lost in percentages, and make minor slip-ups in multiplying/adding probabilities, and this approach eliminates that possibility almost entirely.